Dr. Maricel V. Maffini is an Independent Consultant based in Maryland, US. She focuses on human and environmental health and chemical safety, with special expertise in regulation and policy. Before becoming a consultant, she was senior scientist at Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and The Pew Charitable Trusts, and a Research Assistant Professor at Tufts University School of Medicine. She was one of the key faculty at the ECHO seminar I participated in last May at the Marine Biology Lab in Woods Hole. She is recognized by its leaders, Drs. Pat Hunt and Joan Ruderman, as one of the most savvy people around in public policy.

One thing I will definitely take to heart from my conversation with Dr. Maffini: stay at the table…. “If you want to make change, you need to learn to stick around, make compromises, weigh your answers and options. Sometimes, you need to sleep with strange bedfellows – not literally.” My first impulse is always to work with those who are pure at heart, who are clearly on the side of right, like the marvelous people I am interviewing. Yet humans can be very complicated, neither all good nor all bad, and sometimes prudence supersedes purity in the pursuit of our most important goals. Dr. Maffini’s advice is very timely, and upon reflection, I would work with most people if I had reason to believe that they could be instrumental in protecting children from toxic exposures and environmental harms.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Figure 1: Dr. Maricel Maffini

JMK: What beautiful flowers behind you! Are those rosemary or lavender?

MM: Lavender! It almost matches with my shirt. That’s from my back yard, where I like to take pictures.

JMK: Yes. It looks great – very natural.

MM: It’s from my backyard garden. I like to take pictures in the backyard.

JMK: Are you a big gardener?

MM: I use it as therapy, so sometimes, yes. [We both laugh.] I really like to have colors in the garden and make sure the birds are fed. I like to see them around, especially in the winter. We are fortunate to have lots of cardinals.

JMK: I love cardinals in winter. You are in Maryland by DC, right?

MM: Yes.

JMK: Thank you so much for spending time with me – and for your inspiring talks at ECHO. I hope to get more of your story, then blog it and include it in the book. I was reviewing the things you were sharing with us during ECHO. Maybe it was Joan who said you would be the person to talk to about policy, and I can see why. Having been a scientist and then worked with the FDA, and then become an activist, you really have a clear picture of what is going on in regulatory agencies.

I was thinking of you. I'm on the CHPAC, you know, and we’re writing a letter on plastics. But we are getting a lot of pushback from industry. Because the FDA says that bisphenols in packaging are considered safe, some people think the EPA should not contradict that. So this status quo, and the fact that these regulatory agencies have approved the things in the past just makes it seem like that is part of why it is so hard to change.

MM: Well, on the flip side, the EPA has just banned trichloroethylene (TCE) – right?

JMK: True.

MM: But the FDA still allows it as a solvent for extraction of spices and other things. We have a petition in front of the agency for four carcinogenic solvents that are allowed at the parts per million (ppm) or parts per billion (ppb) levels – for example, methylene chloride to decaffeinate coffee. It’s a known carcinogen. Nobody disputes that benzene, TCE…. But methylene chloride for decaffeination of coffee – we never thought there would be such a strong push-back from the industry. It seems to be a method of decaffeination that is very common. There are others – like water. And not all the decaf coffees have the statement that methylene chloride is used. There was a tremendous push-back from the methylene chloride lobby. Apparently, it’s very commonly done abroad in Germany, and then they bring the decaffeinated beans over here. That’s the process. I was not expecting a lot of people defending methylene chloride.

JMK: Yes – that is shocking. I remember Michael Pollan's Omnivore’s Dilemma. He said that antifoaming agents like dimethylpolysiloxane are added to McDonald’s fry oil, and that a gram of tertiary butylhydroquinone, or TBHQ, an antioxidant that is a form of butane, added to chicken nugget packaging, would kill people outright if they consumed 5 grams of it (Chapter 7). And it is shocking when you learn these kinds of non-food items, and these poisons, are just allowed in food. It's crazy.

MM: Yes. And even though there is a very clear provision in the law that says you should not allow any chemicals that may cause cancer in man or animals after testing, they don't have a system that, for instance, would trigger action. If an agency like NTP (National Toxicology Program) or IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer) or others have a carcinogenic determination for a chemical that is in food, there is no immediate trigger that the agency will act and remove it.

You may have heard about the dye that is called Red 3 – which causes thyroid cancer in rats – we have known that for decades.

JMK: Right.

MM: They banned it in cosmetics in the nineties. In the eighties, they knew already, and they haven’t done anything for food. There is a quote from Linda Birnbaum that says, if you cannot put it in a cosmetic, why would you put it in food? If we would not put it on our skin, how about eating it?

JMK: Right? It's just crazy!

MM: Anyway, I'm derailing your conversation.

JMK: No, no, no – this is right up my alley. I was just in a webinar this week with Tracey Woodruff – and Linda Birnbaum was there. It was a UCSF webinar….

MM: Yes. I had signed up. And then there are so many things happening this week that I couldn't attend it. Linda Birnbaum was talking about policies?

JMK: Linda Birnbaum wasn't speaking, but she was there, and she weighed in on a few things; it was very good, and since you've registered, you can usually get the recording. Veena Singla was speaking, Tracey Woodruff, as well as Sharon Lerner, who wrote that 3M article for Pro Publica.

All right. I will ask my first proper question, because that was just something I was thinking about and wanted to just get your take on.

You've had something of a circuitous route. But how did you get where you are? Could you please describe early experiences that shaped your views and directed you to this place where you're working on this very important problem?

MM: The short answer is I don’t plan. I know what I don’t want. I don’t have a career path – I never did. I don’t have objectives or things I want to achieve. I never envisioned myself leading a laboratory, for instance. I was never interested in being the head of anything. I like to work in groups. That is where I get all my juices going.

I was always curious about how things work. With age and experience, I became interested in the big-picture issues rather than continuing to do research on a very specific part of the body or pathway or things like that. Even when I started years ago – in ‘86 in Argentina – I studied biochemistry there – it was a combination of chemical engineering and medicine – I realized I didn’t want to work in a hospital doing lab work for the rest of my life, doing blood tests and urine tests and all kinds of things in the lab. So I started looking for other things, and that’s when I got into research. I thought, I can deal with this. I’m curious. I want to see where things go.

And then there was an opportunity to come to the U.S. – and here, everything just opens for up for you. When you come from a country with limited resources, you don’t have many opportunities when it comes to scientific exploration, especially in the medical field, where you need equipment and supplies I wouldn’t have access to. I thought, “Really? I can use a single tip instead of reusing and washing and cleaning the tips? I have pipettes for myself? Really?!” It was just a wide-open field to start thinking – and also being challenged on your thinking. The time in the lab in Boston, it was a combination of drilling into scientific questions that never passed through my mind before.

Zooming out, the two people who ran the lab were always challenging us to also look at science as a societal and a political issue. You cannot detach science from the rest of society. Society is influenced by the politics when you start thinking about how you get funded.

So there was this combination of the small work at the molecular or animal level. And then the big picture of how all this can be used, how it can be paid for it. Who benefits? How do we get information from people who are actually suffering from certain diseases? What do they see? Can we help?

That combined with getting tired of the academic world – I had reached a wall and couldn’t go further – I didn’t want to teach or be a head of a lab – I started talking with more and more communities on the breast cancer side of things, and I was thinking there are so many good publications that nobody sees – that are just collecting dust someplace. Without knowing anything about it, I started thinking about how to integrate those two things. I reached out to colleague at NRDC and said, “I am thinking about changing careers. What do you think? Can you give me a sense of who is looking for a scientist?” A few weeks later, she sent me an email saying, this just crossed my desk – and it was a position in DC to work on chemicals and the FDA. So that is in a very winding way how I became all these different people.

JMK: That is an interesting thing about getting older, isn’t it?

You went off to college in ’86 in Argentina – that’s the exact year I went off as well, so we must be in the same cohort.

MM: I graduated High School in ‘85, and in Argentina, we don’t have college. You go from high school to professional schools. So you if you go to law school, and you’re a good student, you can be a lawyer at 22. But it’s scary too!

JMK: Yes – I wouldn’t want a lawyer who is 22. [We both laugh.]

MM: Me either!

JMK: So what prompted you to leave the FDA?

MM: Oh, I never worked for the FDA. I am a thorn in the side of the FDA. I never worked for the agency. When I got that job in DC, it was for the public interest organization Pew Charitable Trusts, who self-funds a lot of the research they do. The project was to figure out how FDA makes decisions when it comes to the safety of chemicals. And we were going to look at the law and at the science.

So they were looking for a senior scientist. That was the position I applied for, and they hired me. They knew about my work on BPA – and BPA is one of the things that was very popular at that time – and still is, I guess. That is how we started.

There was a lawyer who was a project director, another lawyer above him that was the manager of the project, and then there was a scientist above the other lawyer. She was interviewing me and said, “you know, you can’t wear jeans here. You have to wear a suit. Are you ready for that?” I said, I guess – it was not a big deal. You go to the lab to work with rats -- you don’t wear a suit.

JMK: No – right!

MM: At the end, she said, once you leave academia, it’s very hard to come back. I said, “okay – I will take a chance.” I took the chance, and I never looked back. I like working with all of you, but I never regretted moving out. I still think this is the best time of my career – what I have been doing for the last sixteen years.

Pew told us we were not supposed to do any advocacy work – it was just two years of research – and we were required to do at least four workshops with all stakeholders involved. So you have to have industry, academics, FDA, NGOs. We started with a workshop in early 2011 on hazard assessment of chemicals. We went right to the bone. All the people from the trade associations that we were connecting with were expecting us to just push for BPA. They thought the project was a veneer of something interesting, but the ultimate goal was to get FDA to ban BPA.

We never touched BPA at all. There were so many other problems to look at that they were still waiting for it when we submitted the petition in 2022. But that’s how things work. We had everybody there in the same room, very interesting conversations, very heated arguments. We had Tom Sadler, who was an advisor to the group. We have a group of academics and others that were advising our project – Tracey was one – the director at the time of the school of food packaging and other MSU people who had worked tangentially with the food industry.

It was an interesting thing. We would run our ideas by them. We had quarterly meetings. We started creating a record of what the work at FDA is. Problems include the implementation of the law – a very strong law from 1958 with good provisions hasn’t been implemented since then.

Exemptions in the laws have been abused. The lack of information – how they describe themselves as we must know everything – or we do know everything – is not a great attitude. It was the first time ever people who were regulators at the FDA were in the same room with industry, academics, NGOs. They told us they were there because their boss told them to go.

So from then on, we looked at the law, and we looked at the science. And the more we looked at the science, the more we realized that they were just lost. They were using concepts and principles from the 60s, 70s, and 80s. They were a very good progressive agency in the early 80s. They wrote a book on how to do testing for different things – the red book – which is basically a cookbook for how to know what to look for when you do a reproductive toxicity study, for instance – how many animals, what we are looking for, the tissues that you have to collect, etc.

The people who work there are honest people in my view – I haven’t seen anything that would allow me to say or think about corruption. All the meetings that we had with them – nothing ever leaked that we could see. They were private conversations. They are just stuck in their bias towards their work. So it doesn’t cross their minds that a decision that they made in ‘73 with x amount of data, if any, is still protective of the public. They had a hard time understanding that science changes. It’s not your fault. Science is a moving thing, right? And they are operating at a science-based agency, but they are stuck, completely static. The regulatory framework is static, when it is supposed to move with the science, perhaps not at the speed that I would like, but at least some movement. So I don’t know why I got into this rabbit hole, just to say – I have been working with them and getting to know them for 15 years now. That's why, perhaps, you got the impression that I worked there at some point.

JMK: I think so. I saw so many articles that you wrote that were talking about the FDA and how it worked. I kind of thought you had worked there and gotten out -- and then that's how you had the inside view. I think Tracey Woodruff worked for EPA before leaving and critiquing the agency. I might have been conflating that story as well.

I didn't even think about asking you this ahead of time. I don't know why not. RFK? I was surprised that at UCSF’s webinar on Wednesday, Tracey said she thinks he's going to be gone within a year or less, maybe she said, a hundred days. Some people in that webinar were saying, well, if he stayed, he used to have a background that was a little more careful and progressive, and that maybe he could shake things up a little. Do you have any thoughts?

MM: I do. I do think he’s a dangerous guy – based on some of the things he continues to repeat that we all know are not true. On the other hand, based on my 15 years working trying to figure out how to get FDA to move, I wouldn’t disapprove of some disruption. Disruption is good, in a sense, when it comes to chemicals. I’m not talking about pharma because that is something I know nothing about. But some of the things he says – as a colleague of mine said, from time to time he touches reality, and he has very good points.

I ran into one of his videos a month and a half ago. It was a 5-6 minute video; he is standing in a kitchen with all kinds of foods on a counter in front of him – and he is talking about Yellow 6, which is associated with behavioral changes in children. It’s also called tartrazine. So he goes on and on in a very systematic, efficient, and convincing way – to show how many things tartrazine is in, including the medicine that you give your kids if they have ADHD. It’s in the food, it’s in the medicine – and it’s unnecessary. We know it causes problems. So I was impressed by how well he put the message out there with a language people can understand. You avoid it in the fruit loops, but then you have it in your cough syrup. And you may not even know it is there because sometimes, when things are in very, very small amounts, they are not even put on a label.

I’m not sure how long he is going to last. This is like the Hunger Games – but for egos – the battle of the egos. Who is going to be more egocentric? I think the President is always going to win. So he may be gone in a year or two.

He was told he has to show progress in reduction of chronic diseases in two years, which is – why don’t you bring the moon for me over here? [We both laugh.] They are doing all these things. I have more faith he will be confirmed, no question about it – at least four Democrats are going to say yes to him.

I do think the person they chose as a Commissioner of FDA has a potential to do a good job. Dr. Martin Makary is a surgeon at Johns Hopkins, and he gave some testimony at a meeting that Ron Johnson, of all people, put together some time ago in the Senate. He was talking about statistics – pancreatic and GI surgeries – and he asked, “why am I doing double or triple the amount of surgeries in the last 10-15 years? Why do we have all these issues related to diet? Why are we not doing more to prevent certain pesticides being used in food?” He’s not anti-vax – which is good news with that crowd. He seems realistic and thinking there is a “there” there that we are not investigating enough. There are environmental issues that he talked about – ultra processed foods, all sorts of things. My hope is that he may be confirmed and stick around for four years.

To be honest, the first Trump administration did a fabulous job on food issues for chemicals – they granted our petition on carcinogenic flavors with no fuss whatsoever. They did a lot of work on PFAS. We didn’t get much from the Biden administration – the opposite of what people may think.

JMK: That is so interesting. That is something that they were talking about on the webinar as well, that sometimes Democrats are so protective of their own administration, that they will obstruct challenges.

MM: All the studies that FDA published on bioaccumulation of PFAS in the body were in 2018, 2019, 2020. That led to phasing out chemicals because FDA went to industry and said, we have serious concerns that these things are not safe. And they managed to get a compromise. There was a phase-out – FDA gave the companies about five years to stop production, to get rid of their stock – and all those PFAS are gone from the marketplace. In 2016 – at the beginning, so that was under Obama – we got the ban on long-chain PFAS, so it was okay.

JMK: It does surprise me because the chemical that we believe contributed to my daughter's cancer was chlorpyrifos, and at the EPA, that was the first thing Wheeler did when he came in – stopped the ban on chlorpyrifos. And so that is really interesting to hear that it was different at the FDA. And so it really matters who ends up getting in there.

MM: Yes, and the Commissioner matters way more than the HHS secretary. We never heard Becerra say anything. I cannot point to anything that Becerra has done.

JMK: Interesting….

MM: Maybe he did a lot of stuff but in different areas – HHS is such a big place. The fact that the Republicans are talking about the number of chemicals that are allowed – and all the issues with things that are used, and no one knows why – things have never been reviewed – they are touching on all the issues we have been working on. It is always funny to me to see the data we developed put out there.

Because of his own ambitions, the Governor of California put out an executive order with a list of things that he wants to do when it comes to chemicals in food, and it uses some of the information we developed when we were at Pew. So the work at Pew was foundational. We created so much evidence and information that wasn’t there before. We have a spreadsheet with almost 10,000 of the chemicals that are allowed in food that FDA didn’t have – that nobody had. We put it out in a paper in 2013. I’m sure that number now is probably 12,000 or more. We showed that of all chemicals that FDA is in charge of, less than 40% have any data to determine what the safe amount is.

JMK: Yes.

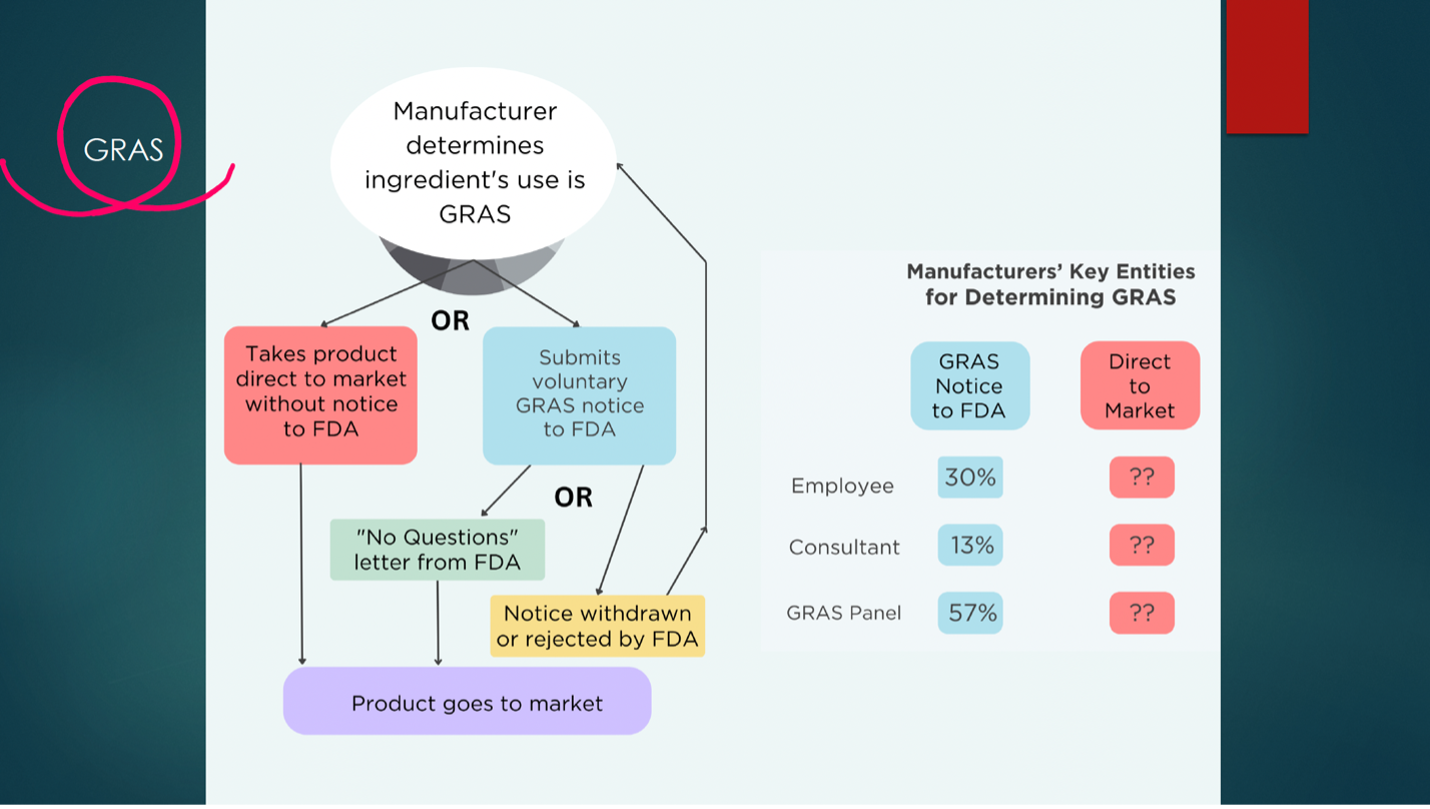

Figure 2: Pew: Fixing the Oversight of Chemicals Added to Our Food

MM: They gave us the time and resources to do all this quiet work that now is everywhere – the issue of conflict of interest. People are now talking about GRAS – the Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) system that is such an abused exemption in the law. You talk to reporters who don’t believe what you are saying. Everybody said, no – FDA doesn’t know everything? Yes. FDA doesn’t know everything that is in food because of that shortcut. The companies are deciding on their own – they don’t have the obligation to tell anybody.

JMK: I remember that from your presentation to us, and it was quite a revelation. It’s the regulatory framework – the loopholes that of course they are going to find and exploit.

Figure 3: GRAS (Maffini 2024)

Figure 4: Problems with GRAS (Maffini 2024)

Figure 5: Conflicts of Interest with GRAS (Maffini 2024)

MM: The Flavors and Extract Manufacturers Association – FEMA – they realized right away that they could help FDA by having their own ongoing panel of experts to review the safety of flavoring substances. These are never a single chemical – they are always mixtures of complex things and also extracts from spices, and things like that. Since the early 60s, they have been running that – they have made way more decisions on GRAS designations than FDA has ever done, and FDA doesn’t even have those safety determinations.

When we were at Pew, FEMA shared with us a spreadsheet with more than 3,000 chemicals they had reviewed. So we got visibility into those as well.

So going back to RFK – I think a little shake-up of the agency would be good.

JMK: It’s good to hear – a little hope –

MM: It’s my silver lining.

JMK: I mean we are grasping at straws. [We both laugh.]

MM: When you mention chlorpyrifos, you know the Biden EPA has been going back and forth.

JMK: I believe Biden EPA had banned it for certain uses, and then that was overturned in court. It’s such a terrible drama. I got a chance to speak to Michal Freedhoff at the EPA’s OCSPP, and she did not seem very interested in really doing anything much effective against pesticides.

MM: I’m not impressed with her tenure. I was involved with that paper with Laura on the EDC screening program, where the second Inspector General report were giving deadlines of 2026, 2028… so really, you still don’t have a plan? It is insulting.

JMK: Yes. As with FDA, the EPA seems to have a lot of well-meaning people who seem to be working awfully hard. They have a lot of meetings. They put out a lot of reports – and yet seem to accomplish so little. It’s interesting.

MM: I think the main difference is that FDA is not a political agency. It may become political starting next week. But it never was. The people who work there were all career people – they are set with the decisions they made – it’s a cultural issue. Multiple times, we would ask them, why did you pick the 90% of exposure to be the most protective? The answer was – this came from the 50s, and this is what we were told: “we protect fools – we protect damned fools – but we don’t protect goddamn fools. That is the rationale. They don’t believe – I use the word “believe” on purpose – that there are non-monotonic dose responses. EPA is the same when it comes to pesticides on the EDSP (Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program) – if it is not a straight line, they don’t care. They don’t think a small amount of a chemical will do anything to you.

JMK: A couple of people I know – expert toxicologists – hold to “the dose makes the poison” – with no exceptions. Okay, really? That old trope? Like you said, people are not moving on with the science over decades to understand some basic things about toxicology. Don’t they read any of the same papers we do?

MM: Yes. It is sad because they keep teaching the same thing in toxicology school. If you take a pharmacology course – non-monotonicity is everywhere. Vitamins are non-monotonic.

JMK: Good example!

MM: The other thing they told us in one of those conversations that they didn’t like to have with us at Pew – and actually, they put it in writing in an email – they said that food additives are safe because they go in food.

JMK: Oh my goodness! What circular reasoning!

MM: One of them who really didn’t like us just resigned halfway through the project. The concept is that we don’t know anything about science – and everything they were saying was in the law – it was not a scientific issue. So it was hard to have real arguments and real conversations.

Laura had written a huge manuscript on non-monotonicity and low-dose responses – we invited all the authors to give a special workshop. There were some interesting highlights, but they had to sit and listen.

JMK: Good. By the way, I was looking at this most recent editorial that you and Laura wrote for Frontiers in Toxicology, and I just wanted to say I really enjoyed the way you all framed it, and thought it was excellent communication: “Exposure to a myriad of chemicals, starting prior to conception and continuing until death, has likely contributed to an epidemic of non-communicable diseases seen throughout the world.” I think going broad like that was very helpful, very insightful. Maybe I will quote you in the book.

MM: Thank you. It’s been very nice to play with Laura. Such a bright mind!

JMK: Absolutely.

You've done so much, and you've written so many excellent articles. Is there one thing that you would say you're proudest of? Or maybe a couple of things?

MM: In this space?

JMK: In your life!

MM: Looking back – I’m proud I didn’t chicken out. I always said when I left my country to come here, I used pretty much all my chips assigned for risk. I have a limited amount, and I used them all when I came here, and then I didn’t go back home. That allowed me to make other decisions. But I am risk averse. However, I am proud that I’ve been able to get over that and move in so many different directions.

My husband would probably disagree that I don’t take risks. In certain things – when I have a gut feeling – I move, and this is what happens.… We took the chance to move to DC for me to go to this place – and he followed me. He’s a teacher, so he found a job at a good school – he’s still teaching there.

Then when the time came, where I had to start working on my own, I was offered a job right away in California – but we talked as a family—it was not a good decision to move there. He told me, if you stay here, you will never run out of work, and he was right. I was terrified – we were moving from two salaries to one salary, almost immediately. And then I went from one contract to the next one to the next one. People started to hear about what I was doing, and I would get more work. I managed to survive for 15 years as an independent consultant doing the work I like and writing about what I like. The moment I left an organization, I felt I could finally say what I wanted to say. I didn’t have the constraints of an organization that has a mission and donors and other things that mean you have to tailor what you say. I am free to say what think.

JMK: That is really wonderful.

MM: It was liberating.

JMK: Absolutely. I'm thinking about these things myself, because I could really get in trouble with a book called, perhaps, Poisoning Children: How the Petrochemical Industry Has Imperiled the Lives of Every Child on Earth. If I really go for the jugular – well, we all know people who've been targeted by the industry, and it's terribly unpleasant. Is that something that you also worried about?

MM: No. Going back again to Pew – those were my training years – I learned that if you want to move the needle, you need to be able to talk to everybody, even the people who are in the complete opposite positions. If you walk away from the table, you are out. So the solution is staying at the table, pushing back in a manner that is rational, dispassionate, diplomatic – even though in my private life I’m not necessarily diplomatic.

One of the first things they told any new employees was that Washington, DC is a relatively small place. When you are in a public space, be careful what you say because you never know who is listening. If you are at a bar or a restaurant…. I remember the first time Laura came and stayed with us, probably a year into my work. We went out to a Mexican restaurant. She was asking me all kinds of questions about the new job, and I was giving her rehearsed answers. She asked, “Why are you talking like that?” I said, “let’s go home.” [We both laugh.]

I learned this, and it has paid off. I don’t remember anybody who has contradicted any statements I have ever made. I don’t like certain people. There are a lot of people who may not like me, including lots of them at the FDA. But I carried that thing from the years at Pew. If you want to make change, you need to learn to stick around, make compromises, weigh your answers and options. Sometimes, you need to sleep with strange bedfellows – not literally. [We both laugh.] But that is how the process works. I am proud I have great connections in industry, that I have never had any issues with Sherwin Williams, the company with whom I’ve been working for more than ten years. I have connections in multiple NGOs. Nobody has ever – that I could see – pushed me away or left me out of conversations because of the work I do.

JMK: That is really, really a valuable perspective for me personally, right at this moment. I think that's such a hard balance to strike. I was at that webinar asking for advice on this as well, because one of the speakers was talking about whistleblowers, and her overall advice was, don't do it if you can avoid it. It’s interesting to think about – how do you say what you need to say? How do you think of multiple audiences and not get into trouble? One of the things she said is, make sure that everything that you write is correct – which we all know from Rachel Carson. You have to double-check, triple-check everything.

MM: Yes. Absolutely. Last night, I was talking with a colleague, asking him to double check with me in a response to a reporter. We still do that, especially when they may change something. Can we start talking more strongly about GRAS and the horrible things that does to the system? Who is listening? What is the ground-swelling? The ground-swelling at this time apparently is bipartisan. So how do we take advantage of this opportunity? Just because you vote one way, do not dismiss opportunities to move on the issues you really care about.

JMK: I think that is wise.

Okay, the next question is this: it's a difficult subject that we work on, right? There is a lot of fear and guilt, and especially relating to children – as I'm writing about. And I wondered, is this a topic that has caused you anxiety in the past, and how do you pitch it to others -- something that is so important, but also productive of anxiety among many readers and others?

MM: It hasn’t given me anxiety. I eat everything – we have frozen food, and we have canned food in the pantry. I don’t go out of my way to buy organic food because the message for way, way too long from some of my colleagues was buy organic. That is the solution to everything. It pains me because it is a very white, East Coast – West Coast message. The middle of the country often cannot afford that. A message like that was, in my view, hurting people, making people feel guilty because they couldn’t afford the things that would protect them if they were pregnant or their children.

I eat, and I work to change the system so we all have the same opportunities to have safe food that will not make us sick, that will not give children Type 2 Diabetes when they are six years old or a fatty liver when they are fifteen. We cook at home. We don’t have much processed food – but it depends on the week and how busy we are.

Everything else – I always try to say, your job is to feed your family. You don’t need to be a scientist or a chemist to figure out which foods are safe for you and your family. That is the job of the food manufacturers and the FDA. I don’t go out of the way to buy specific brands or foods. I try to talk the talk and walk the walk.

JMK: That is an interesting perspective. And quite different from Genoa Warner, for instance, who, with her young children, is trying so hard to make good decisions. But yes, it's a dilemma.

MM: I can afford this because I am past the time of having children, and I never had children. But I do care about the children that my nieces are having. I cared about them when they were young – in a different country. I see the rest of us here as part of a bigger family. I want the same opportunities for everybody. That’s why I want to change the system.

JMK: Love it! I wish I could appoint you to FDA. [We laugh.]

And what if you were appointed to FDA or EPA – if you had that opportunity? This is the next question. If you could single-handedly recreate US policy on chemicals, what would you do?

And then, the more down-to-Earth question is, given that we already have these systems in place, what would you change going forward? Clearly, some things you've identified – the GRAS exemption and other exceptions and loopholes. But I just wonder how you would answer this question that seems so much in your domain.

MM: If I have a magic wand, the first thing is to require information be given to the agencies – EPA or FDA. They both need information – and it should be a mandate; it should be required, not recommended. There should be a team that would perform pre-market assessments. There would be opportunities to correct issues with industry because we all make mistakes.

But there should be lots of public information where you can see all the ingredients that are in your Cheerios – what they are, the ingredients, the processing aids, and everything, because there is a lot more than what is on the box. Those small amounts account for something – because this is the same chemical that is used as a processing aid in 15 different things that are very common in the American diet – and the small amounts add up.

The other thing is that chemicals should be looked at as classes based on the common toxicity they have. We should stop doing the silly thing of one chemical at a time. We don’t eat one chemical at a time. We eat a diet – a complex mix that has multiple things that may be contributing to a hazard, to a function of an organ, or a gene expression or timing, whatever it is.

I think the other issue is that the safety of chemicals should be based on developmental exposures. We are screwing up an individual before it is even born. This is hypothetical because I don’t like to kill animals anymore – but all the experiments should be based on whether or not there are developmental toxicities in both the pregnant animal and the pups. And what happens to those pups when they are born? We should be looking really at the chronic intake and the chronic effects that can come from those ongoing exposures.

That’s what Congress was concerned about in ’58 – the chronicity of exposures and the development of chronic diseases. That’s important – looking at chemicals cumulatively, and in classes, where you actually determine a safe amount for a class. That class could be 5, 15, or 20 chemicals – but you cannot go above the safe amount for all of them, rather than each individually.

So protective issues like that – closing the loopholes – as you said, on GRAS – is important. It’s just silly that the agency that is in charge of protecting public health doesn’t know what is in the food.

And then we have these random things like the tara flour intoxication, with people needing hospitalization and surgeries to remove gall bladders, and the extract from one poisonous mushroom that was added to chocolate and gummy bears that likely contributed to the death of a few people – and many, many hundreds hospitalized across the country. All those things somebody at some point said, let’s do this – this is safe, and then we end up with this crisis.

People putting caffeine in an alcoholic beverage sold to young people where then they were drunk and sleeping and being run over by cars because they couldn’t figure it out – the mix of alcohol with caffeine. It was just insane that those kinds of things can happen, and that the agency didn’t know anything about it. There are real-life consequences.

Then the other thing to change is the mentality. The agency is still in the mode of poisons. They look at death. They don’t have a framework for understanding chronic effects, so if it doesn’t kill you, it makes you stronger, says the song.

But they pay way more attention to pathogens, to bacteria, to contamination, of course, because that could change your life in 24 hours. But then we have this burden of chronic diseases, non-communicable diseases that we don’t know what to do with now – and we are completely overwhelmed. The system is so overwhelmed.

We have all these issues, from mental health to diabetes, obesity, and metabolic diseases. No one ever stopped to say, why is this happening? Why do we have to pay a gazillion dollars for health care when prevention is so much cheaper?

JMK: That is so true. I have a keen eye on things like cancer and autism, these things that have profound effects on people, and that we think we could prevent in most cases. And it’s such a shame.

MM: At least let’s try something. Does it work? No? Well, we may need a different intervention.

And as I mentioned earlier, this is a science-based organization. We should move with the science – if something doesn’t look the same, consumption patterns have changed, then let’s review it. Nobody is going to throw rocks at the FDA because they are taking care of people.

That is the main concern they told us they have – “we cannot reverse something; the people will kill us.”

JMK: Yes. I think they are wrong.

MM: Yeah!! [We laugh.]

JMK: From what I have seen, the EPA is like that – there are so many chemicals, and I think it is just overwhelm. And maybe that is one reason they don’t want to revisit decisions. It’s just crazy how many chemicals are out there. One thing I learned at ECHO that I had not seen before – and I did look up a source for this – but there are 350,000 synthetic chemicals in production, rather than the 80,000 previously mentioned. It’s just so many chemicals.

MM: When Congress passed the law for food, there were 300-600 chemicals in use. And now, we have maybe 15,000, without including all those that are in the dark, that nobody knows.

JMK: 15,000 in food?

MM: Probably. When we last published a spreadsheet in 2013, we had roughly 10,000, including pesticides and all the indirect additives, all the GRAS substances. 3,000 were flavors. I don’t know if you have ever seen this clip from 60 Minutes, which is probably 10-15 years old. One of the old reporters [Morley Safer] was doing an interview with Givaudan, which is the largest flavoring company in the world.

So they were walking through an orchard, and they were talking about – this orange has the essence of this – it also smells a little bit like vanilla. And then they were talking about the number of chemicals, and they went inside the lab. And you have a drawer with probably 500 different flavors of cherry.

JMK: My goodness!

MM: So everything is chemistry; nothing is coming from that beautiful orchard where they were anymore. They may take a new type of mandarin or something, peel it, and extract the oils, and see what else they can do. But then, it goes immediately into a chemistry lab. I will check if I have the link.

The reporter was very shrewd because he said, “well, all these things make the food be delicious – and so people eat more of it.”

“Exactly” they said, “we want them to come back– that means the flavor is successful.”

“Oh, so it’s an addictive behavior,” the reporter affirmed.

“Yes,” said one. “That’s a good word for it.”

“No! We wouldn’t call it that,” said the other. That is exactly what they do. It’s all about what is in your brain.

JMK: Wow! I talked with Laura Schmidt at UCSF, and she works on the hyper-palatable and ultra-processed foods, and she really makes the argument that it is intentionally addictive. I noticed Tracey Woodruff at UCSF just sent out an announcement that they are creating a new Center to End Corporate Harms.

MM: Ha! Only Tracey.

JMK: It boldly includes all health-harming products: fossil fuels, plastics, tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed foods.

MM: Including ultra-processed foods? I saw it on LinkedIn – I got it from Nick Chartres.

JMK: Yes. Laura Schmidt is the one in that group that is talking about ultra-processed food as a corporate harm. It certainly intersects with your interests.

MM: Definitely. There was a webinar mid-December – joint NIH and FDA – on nutrition. FDA has undergone reorganization, and they now have a Center on Nutrition. What before was Food Safety and Advanced Nutrition (CFSAN) doesn’t exist anymore. Now there is an Office for Food Chemical Safety, Dietary Supplements, and Innovation and one for pre-market assessments and post-market assessments. It’s coming – the comments on that are due on January 31st.

I was on a webinar on Tuesday, and there was a gentleman from Virginia Tech who was the spokesperson for the Institute of Food Technologists – which is supposed to connect all the academics in the food-related departments at colleges and universities – but it’s basically a food industry mouthpiece. What is coming to push back on processed foods is the exact same argument that is used for chemicals or tobacco. It’s the same playbook. “We cannot do anything until we have a definition. We cannot do anything until we know how it works.” The last one is, “There will be unintended consequences. And each individual food will have to have its own definition.” They have the playbook, and they are going to use it to block every effort on ultra-processed foods.

JMK: It's so insidious. And I noticed some small differences from Naomi Oreskes's work, The Merchants of Doubt. I mean, it's even refined beyond that. They're finding more and more ways to stall.

MM: There are two women who run something called Unbiased Science. I found them because it was liked by the person at FDA who makes decisions on the safety of chemicals. She liked what these people write. It’s a funny name – “Unbiased Science” – because they are absolutely horrible – they use this mantra that everything is chemicals – they start describing the chemicals in a banana….

JMK: Yes.

MM: “Therefore, everything is chemicals. Therefore, PFAS are chemicals. Phthalates are chemicals. Acetaldehyde is chemicals. Formaldehyde is chemicals. We are all made of chemicals. So nothing is going to hurt you.”

JMK: I hate that one – it just gets under my skin.

MM: I was so livid. I almost wrote something to publish and then said nope. I said, there are certain things I don’t write. I don’t write about politics in my social media.

JMK: I try to avoid it. I don't think I'm going to be able to avoid it entirely.

Okay, just two more questions. One is, what do you think will be the status of children's health – or your perspective is more everyone's health – in the year 2050?

MM: I want to be optimistic. It is likely we will reach a critical point, a breaking point, where someone will realize we are just not giving our children the same opportunities we have, that our grandparents had, and that is unethical.

From then on, we may do better. I don’t know when that critical point may hit us. Probably, and this is just a hunch, it would be related to the inability to recruit new soldiers because of their health – they will be already sick. Metabolic diseases are most likely – liver issues, kidney problems. All those things – we see them already in children. Based on this country and how it operates, that may be a breaking point.

There was an attempt at Pew – they were working on school lunches. Some of the main supporters were military people – Brass – high in the ranks because they already had trouble in the 2010s to recruit healthy people. And unfortunately, they also usually come from backgrounds where they don’t have any possibilities when it comes to good nutrition, with nutritional deficiencies and environmental exposures, and you name it.

If I want to be very skeptical and dark, it will take not enough soldiers to send to war that will produce change.

JMK: You said you were going to start optimistic. But that is very dark.

MM: Well then I took a turn. We need that breaking point. The status quo, tinkering at the edges, doesn’t work. Sometimes I use the analogy that kids used to be born at your own one-yard line in a football field where the opposite end would be disease. We have a long time to go to get sick. Now I think kids have been born, some of them, at the 20, 30, 50-yard line. So the expectation of being healthy for many decades is much lower.

We are exacerbating things – things are happening more quickly. The former Director of the Office of Food Additive Safety was at that workshop with NIH and FDA, and she said, there are things we can do – but there are things we cannot do. With all the chronic disease we have, we have to be sure of how they happen before we do anything. Really? Seriously?

JMK: Yes – that’s awful. That’s the opposite of the precautionary principle.

MM: When you start seeing chronic diseases like Type 2 diabetes that used to show up in 65-year-olds and are showing up in a six-year-old kid, how can you say they take a long time? Diachronicity is becoming an urgency.

JMK: Yes – I could not agree more of course. All these cancers that are showing up in younger and younger people, not just childhood cancer per se, but also colon cancer, breast cancer. We're seeing so many younger people getting cancer during really pivotal, important life years. It's just terrible. I am surprised with the number of people who have these diseases that anyone can say that and not have someone in their life who they could look to as an example of someone who's gotten these diseases quite young.

I hope we do have a breaking point – on climate change too. I thought the breaking point would be Katrina. Then I thought it would be Sandy. Then I thought it would be Paradise, the fires in California. We keep waiting for breaking points in all of these environmental crises, and the capacity of human beings for denial is just enormous and befuddling.

MM: Yes. We make up some different stories. I thought it would be in North Carolina in the mountains – Asheville – that was completely wiped out. Maybe Republicans would start to make sense. Nope – rebuild, rebuild, rebuild. They save money to pay for it.

JMK: And the news broadcasters say funny things with like, “Oh, modern fires today or modern hurricanes….” But they don’t say the words “climate change.”

Well, you've been so generous with your time. But the last question is, do you have any questions for me on my project or my experiences?

MM: I would love to know more about it – I know what is driving you. But I would like to know more about your story.

JMK: So about Katherine. I was in science as an undergraduate, and April of senior year, I was deciding between medical school and graduate school in literature. I went with literature, and I have loved being a professor.

But then, when Katherine was diagnosed, I turned back to my science background to try to figure out what had happened. I became an activist, and after she died, I kept going with that, but then realized I needed to get a credential. So I went for the Master's in Public Health at my own institution. I could do that and still be a professor, and I learned more than I ever thought I would.

To me, there was this huge gap between what the scientists know about childhood disease and environmental exposures and what ordinary people knew. I didn't realize how unprotected we are. I really was a very trusting person, growing up. I trusted government to protect us. I trusted that older generations were looking out for us. And so that's when I started working on this project – a long time ago.

Really, my first literature searches were because of Katherine. You know, we believe that her leukemia was caused by exposures to chlorpyrifos both before I was pregnant in an apartment, and then sprayed for mosquitoes all throughout her childhood. We just did not realize until later, putting the pieces together, and it was too late for her. I wanted to make prevention her legacy.

She was really quite brilliant.

So the book is putting together stories of kids who have endured these outcomes, trying to appeal to people's sense of ethics. It is wrong to be doing this to children.

I pair that with literature reviews and the rather inspiring stories of people like you, like all the faculty at ECHO, who've been working hard on these problems all along. As you said, so many of the studies just sit there and gather dust – but not for lack of trying. And I think the hopeful message is that if we put these pieces together, we have the information to make better choices. We have to persuade the general public that that is the case. And so, some people don't believe that there is a connection between these chemicals and disease. Others believe there's nothing we can do about it, perhaps. And I think that's wrong.

So that's the project in a nutshell. I have to say. I'm thrilled to have a contract with Johns Hopkins. I'm really hopeful that it can reach more people than I would have settled for.

MM: You said something that I was thinking: there is a lack of literacy. I don’t think I particularly do a good job helping people understand the issues. And what the reporters are usually asking is, what can we do? What they want to know is which food not to eat? Which appliance not to buy? That is okay, but why are they asking us what to do? The public is supposed to be protected by the different agencies at the governmental levels – local, county – all the way to the top.

JMK: We certainly have enough of them.

MM: Yes. So I just don't know how to answer that question anymore, because it's not our job. And I applaud you for being an activist in this way and not giving up. Because it takes a toll.

JMK: It does.

MM: I know it takes a toll on me.

Sometimes you're just exhausted. How many times you have to say the same thing over and over again. But I have a strong Italian background, and I am like a dog with a bone. I keep going. But I would not be able to do what you do.

JMK: Well, that’s very kind. You are doing your own thing.

Here’s something inspiring. The next person I'm going to talk to yet this afternoon is Sharon Lavigne. She's an activist in Cancer Alley and has fought back against the poisoning of her community. She actually got one plastics plant and another chemical plant to not be sited in their community. And something she said really struck me; she said, “The more they said there was no hope, the more something in me got riled up.”

But I completely agree with you. It takes a toll. It’s difficult and frustrating. But I’m resigned that that’s what my purpose in life is now.

MM: I salute you.

JMK: I salute you right back. It's been such a pleasure talking with you this afternoon.

Well, have a wonderful weekend. Thank you!

MM: You too – take care!