Dr. I. Leslie Rubin, MD, is an Associate Professor in the Departments of Pediatrics at Morehouse School of Medicine and Emory University School of Medicine. He is the founder of The Rubin Center for Autism and Developmental Pediatrics in Atlanta. Originally from South Africa, he attended medical school there and then completed his training at Case Western. He became a professor at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School before moving to Atlanta.

Dr. Rubin is a Developmental Pediatrician who cares for children with developmental disabilities and works with the Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit (PEHSU) at Emory. He is the primary editor of Health Care for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and author of many other books. For almost 20 years, he has created an amazing interdisciplinary, international environmental public health program: Break the Cycle. The program enrolls college and graduate students who get local mentors and complete projects on environmental health disparities over the course of a year. Everyone who is accepted comes to a meeting and presents their projects, and then they combine these for publication in a journal. Many of these students are now succeeding in college or law school, and the program received the US EPA’s Children’s Environmental Health Excellence Award in 2016.

Dr. Rubin has served on the Board of Scientific Counselors (BOSC) to the EPA Office of Research and Development (ORD), the National Advisory Council for Children and Disasters (NACCD), and the Children’s Health Protection Advisory Committee (CHPAC) to the EPA.

Dr. Rubin says his personal mission is “to work in collaboration with others on reducing children’s health disparities and promoting health equity for all children, locally, nationally, and globally in the context of environmental and social justice and in the face of climate change.” He is a charming man with a global view of children’s environmental health, and I have really enjoyed talking and working with him on the CHPAC.

JMK: Hey, Leslie! So good to see you again. I have a list of questions, but we can stray from them. I really just want to hear your stories, especially since you grew up and were trained in South Africa, and then came here. What in your childhood or early training first got you interested in children’s environmental health? How did you get where you are now?

LR: How much time do you have? [We both laugh.]

I knew from a young age that I wanted to be a doctor – at that time when I was growing up, if someone was ill, the doctors would come to the house with a black bag, with magic stuff in there to make people better. So I always knew I wanted to do that. I saw people having difficulty, getting hurt and fixed or getting sick and then getting better. So I thought, that’s what I want to do, and it stayed with me.

So I went to medical school. In South Africa, it’s a six-year curriculum for medical school. The first year covers zoology, botany, chemistry and physics. The second year was anatomy and physiology. The third year was pathology and pharmacology, and then the fourth year, you enter the clinical realm.

The first time I entered the clinical setting of a ward, and there were people very sick – dying – including one just a couple of years older than me, it really blew me away in a powerful emotional sense. Instead of making notes about the clinical conditions of the patients – this one has lung cancer in this lobe or that lobe – I found myself writing about how the patients must feel to have these conditions. It was distracting to have to do things that may have hurt people – but it made them better. That was a struggle. Needless to say, I didn’t learn as much as I was supposed to, but I managed to pass all my exams.

When you graduate, you don’t get your license immediately. You have to complete the internship year – six months of internal medicine and six months of surgery or six months of obstetrics and gynecology. My first six months was in surgery.

Let me paint the picture of surgery in the hospital where I worked: South Africa being an apartheid state meant that there was complete separation between Black people and White people. The sad reality was that it was exactly like Jim Crow laws in the USA. There were hospitals for White people of European extraction and hospitals for Black African people. There were places to live for White people and places to live for Black African people. The only time you would interact is in a master-servant relationship. You are also dealing with overwhelming poverty. I lived in the suburbs of Johannesburg; the city of Johannesburg was mainly the business part of the city, and then there was another area – the city of Soweto for Black people – a city created for apartheid – the acronym for South-West Township. They had the Black people live there. The crazy thing is that to get anywhere, they had to take buses out of the city. They had to walk miles and miles. It was hard enough, and the living they earned was very meager. How they survived, I don’t know.

My first experience was working in the surgical unit as an intern in the hospital, and it was more trauma than elective surgery. There was a lot of violence associated with poverty, particularly on a Friday night after people got paid and got drunk and went on rampages. It was terrible – the violence was horrible. The part that is very different from the violence in inner cities in the U.S. today, is that it wasn’t gun violence because guns were very expensive. So they used knives or whatever sharp or heavy objects they could find – axes, knives. There was a practice of putting bicycle spokes into the spine to cause victims to be paralyzed.

As a result, there were many men who were paraplegics, and there was a paraplegic basketball team, which was an amazing thing in the hospital. That program was run by a physical therapist, who was a woman of Austrian or German or Dutch extraction and had that Nordic determined and strict quality, and she organized the basketball teams plus exercises.

Another common practice was to stab people in the chest, which punctured the lungs, so in order to treat the punctures, they put in a tube to drain the air, and it bubbled into a bottle under water, which was very effective. There were no machines. And so you would have many of these men walking around holding jars with tubes by a make-shift handle. It sounds almost comical, and it was surreal.

Another phenomenon was, because people were in the depths of despair, they would drink alcohol. As there wasn’t any place they could legally buy alcohol, they would frequent illegal homemade ‘distilleries’ called Shebeens where people would make their own alcohol. They would make a big drum of it, and people could have a cup of it. But who knows what they put into it? So many people came in psychotic. In the hospital, nurses would put a strip of tape on their foreheads or on the back of their hospital coats that said, “If lost, return to building 4.” There was no psychiatric facility, so these patients just wandered around the grounds. So that was my first six months.

My second six months was obstetrics and gynecology, and I loved obstetrics – I really did. It was so great to deliver babies. And that’s all I did. I was on call for 36 hours, then off a day, then 36 hours on again. I would come home, and I wouldn’t even be able to lie down. I would just fall over. It was very, very busy. There were a lot of healthy babies born, but it was like a factory because that was the only place they could go for two million people and one hospital in Soweto. I liked it. We used to be up all night with Caesarian sections – all kinds of dramas you might not want to hear about. The only problem was that when the babies were born, that was the end of my relationship. I enjoyed it but decided that wasn’t exactly for me.

I had to do six months of internal medicine, which was a whole other story. The hospital at that time was a converted army barracks which became the ‘wards,’ so all services were at ground level – that gave the patients freedom to wander around, whether they were carrying their bubbling bottles or had stickers identifying their location. The hospital was so busy that when we did an intake, there were times when there were patients in the beds, patients on the floor between the beds, and even some patients under the beds. It was so crazy busy.

There were lots of serious diseases of many varieties. It wasn’t what I particularly enjoyed, but I learned a lot. And then for my last six months, I did pediatrics. When I did pediatrics, it was a whole different world. It was not all wonderful because the sad reality is that there was a very high rate of malnutrition and infectious diseases. In the summer, the kids would get diarrheal diseases and become severely dehydrated very quickly. They would come to the hospital at the last minute, and we would try to put in IVs and rehydrate them. The sad thing was that we would admit them to the ward, and the next morning when we came to the ward, a certain number of them had died already. So it was very, very tragic.

In the winter, they would get measles epidemics. So everybody used to get measles, and it wasn't like, you just have a rash and you stay home. The kids that we saw in the hospital would have complications like pneumonia or encephalitis, and often, the measles would exacerbate tuberculosis. So we were dealing with very serious conditions.

But I will say that it drew me to this group of kids. I did 6 months of each discipline, and I thought – just to wrap it up – I will do some psychiatry, so I went to interview, and the psychiatrists who were the head of the department were totally crazy – I decided I could not work with them. So I said, thank you very much – I changed my mind. There and then, I went into pediatrics and did my residency. It was again dealing with malnutrition and diseases common in developing nations.

The way it worked during residency, I would be at the Baragwanath Hospital for African people in Soweto, and then I would be at the hospital for White people, and then there was another hospital for people of mixed race and for Indian people, because South Africa has the highest Indian population outside of India. So I worked in the three different hospitals, each for a different segment of the South African population, each with different cultural and socioeconomic status and with different diseases.

When I completed my pediatrics training, I was interested in two areas – one was the newborns because as I finished my residency, the whole new advance in newborn care arose with incubators and new knowledge about how to care for the fragile newborn infants, particularly those who were born premature. I was fascinated by that. But I was also intrigued by neurology, which was dealing with the brain – so I did another six months in the neurology unit.

I saw sad things, particularly among the adults. At that time, there was not much treatment for many of these adults – they just stayed in the hospitals. I used to order a glass of wine for them at night as a prescription. And I did pediatric neurology as well. The head of neurology had trained in Boston, and he used to consult to a school for children with cerebral palsy, so I would go with him to the school. That was my favorite part, not just because of the complex problems the kids had, but because of the interdisciplinary approach to management. They had the neurologist, the physical therapist, the occupational therapist, the speech therapist, and the teachers. I thought that was the best.

Then I had applied for a fellowship in neonatology, and I landed a position at Case Western in Cleveland, Ohio. This is where things became rough and tough for me.

I had come from a very warm climate with a warm and nurturing extended family and community, and I took it all for granted of course. I ended up in Cleveland with a wife and two young children – and I didn’t know anybody. I got to work – and I had to work every third night. And I didn’t know anybody to ask, where should I buy a car? What should I do? How should I go about things? I was totally disoriented and quite depressed, particularly when it was winter. Cleveland in summer was hot, humid, hazy, and unbreathable, and when it rained, I thought it was going to clear up. But it got worse. Then Fall came and blue skies appeared, and then the wind blew, and it was cold, and then all of a sudden, in October, the snow started, which was exciting. But then the snow continued and continued, and the weather was absolutely freezing cold.

The thing that really gave me a jolt to my soul was when daylight savings ended. We measure our days by how it looks outside. At the hospital, one day immediately after the end of daylight savings, I looked outside, and suddenly it was nighttime – and it wasn’t supposed to be like that. I just freaked out inside. I didn’t do anything that was noticeably abnormal, but from that moment, I went downhill emotionally. I really had a hard time, to the point that the director of the program came to my house one night to see if I was okay.

While I was doing that, I realized that for me, neonatology was very tough. There is a lot of detail. You have these tiny fragile little babies, and you have to give them just the right amount of fluid and electrolytes and glucose. You have to feed them and breathe for them, and all of these things are very detailed. Also, you had to be on call every third or fourth night, which was quite exhausting. And so I said to myself, I don’t want to be doing this in 20 years.

I completed the year and then took another fellowship in what was called Care of the Handicapped Child. That was very much like what I experienced in my neurology training – children with cerebral palsy, spina bifida, cleft palate, orthopedic deformities, or other genetic syndromes. At first, it was a challenge to deal with children who have major physical and facial differences and disabilities. But I found it really very interesting and complex. As I now reflect, it triggered my interest because I like things with complexity, and I also like continuity. With this specialty, the children return for follow up every month or two, so you get to know them and see them – and help them make progress. We had a whole clinical inpatient unit, where the children would be admitted for their medical conditions as well as surgeries, and we would get to know them very well and monitor and guide their progress and improvement.

You’re recording this. This could be like a memoir – nobody ever gives me an hour to tell about myself!

JMK: I am enjoying this so much.

LR: So I really got into that very much, and it was there that the director invited me to stay on as faculty. And then he asked me to become a medical director of a facility for people with disabilities. I was in charge of the medical care for all these people, so I hired a nurse practitioner and another physician – and together we did a good job. And then one day, we had a visitor from Boston – Allen Crocker who was the Head of the Developmental Disabilities program in Boston at Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. I had to be his host because my boss had been away, so I spoke with him and hosted him and told him what I was doing. And he said if I was ever in the Boston area to let him know, and I should visit his program there. So I said, okay, we will be there in July – and I could stop by then.

When I visited, I spent the day with him, and he introduced me to the staff, and at the end of the day, he asked, how would you like to come work here? I had been trying to get out of Cleveland ever since I landed there. That was very exciting. That was like, Jean-Marie, some divine gift for a lot of reasons – first, to get out of Cleveland, which was very depressing – second, to work at Boston Children’s, Harvard Medical School, which was prestigious. And then third was to be in a place where there were blue skies. And, although Boston is cold, there are beaches, and much to do and see.

JMK: Beautiful!

LR: Also, here’s another perk – about a dozen of my medical school colleagues were also in the Boston area, so I wasn’t so alone and isolated. So I had a good time there, and I learned a lot in the process.

I’m going to show you something. Allen Crocker, my mentor at Children’s Hospital in Boston and I published a couple of books on medical care for children and adults with developmental disabilities: Medical Care for Children and Adults with Developmental Disabilities. The first one came out in 1989. I had done one with the Cleveland group on cerebral palsy in the early 80s. We did the first one ever – it was a best seller, and people would bootleg it, make photocopies. What I showed you was the second edition, and then we did a third edition. I said I would never do it again because – you see how thick it is? It’s a big book. So and here is the third edition [he shows me a huge two-volume set].

JMK: Oh my goodness!

LR: You can imagine – I was totally finished.

JMK: Was it just that the field grew so much? Or did you feel that the publishers were pushing you to make it longer? Or was that just the project?

LR: It’s just that we learned more. I will show you another example. I don’t have the original with me, but Pediatric Environmental Health, 4th edition by Drs. Ruth Etzel and Sophie Balk is about four inches thick –1200 pages. The original book was about half the size – about an inch – 200 pages. The point is that as we learn more, we understand more and have more knowledge and appreciate the complexity more, not just from a medical point of view but also from a psychological and social point of view that adds understanding, dimension, and appreciation for what needs to be done. So I said, never again after that, but a few months ago, I had a call from somebody asking, are you thinking about a fourth edition? I said absolutely not – I wouldn’t dream of it – it was nightmare. I had PTSD after it. We had a few conversations – we had already got an okay from the publisher – and in the end, I switched and said yes. I am dreading the thought, but there is going to be a fourth edition. I am going to assign a lot of the work for it because I read every single chapter of that third edition. There were other editors, but I was the ultimate arbiter to make sure of quality and consistency.

JMK: I know many of those books are put together by multiple people because it's just too much for one or two people.

LR: Yes – we had multiple contributors.

After Boston, I was invited to come to Atlanta to head up a Developmental Disabilities program at Emory University. It was very exciting – I had had enough of the snow, and it was nice to go to a sunny place. It was like going home because the weather was much more familiar – sunny, less cold, with longer days. And there were a lot of South African expatriates in Atlanta, so it was like going home. It was quite a treat.

As part of what I did, being the medical director of that program, I set up a lot of different clinics and programs, one of which was a cerebral palsy clinic in Atlanta in a hospital in downtown. In the downtown areas in the 1990’s, most people were African American and poor – much like the hospital I worked at in Soweto in Johannesburg. I liked it because it was complex and required thought. When we established the clinic, we decided we would use the CDC documentation to keep track of the patients. After a couple of years, I got some funds, and I said I would like to see what the problems of the kids had been. I had been thinking about the number of illnesses, emergency-room visits, surgeries, medications, specialists, and hospitalizations. That’s the way my mind worked with my medical training – and that was a lot of the data we actually got. Except there was something I had not counted on. What we realized was that most of the children with cerebral palsy were born prematurely to mothers who had either taken alcohol or other drugs or tobacco. 50% of the kids were living with single mothers, 20% with grandmothers, 10% in foster care – and only 20% with a family with two parents. It made me realize that what I was dealing with was not just taking care of patients – there were a whole lot of things that came from upstream that caused these problems and compromised these kids’ optimal care because of poverty and living conditions. After working with a couple of the students and researchers, I came up with the concept of disadvantage, which was social and economic, and disability, which was the cerebral palsy and other disabilities, and I conceived of this as an intergenerational cycle.

Let me see if I can find my original diagram, which I am going to show you right now.

JMK: Wonderful! We talked about this at the CHPAC party, and how I've been so interested in circles and cycles. And I visited your website. I just think it's the right way to think of these things. I would love to see the original diagram.

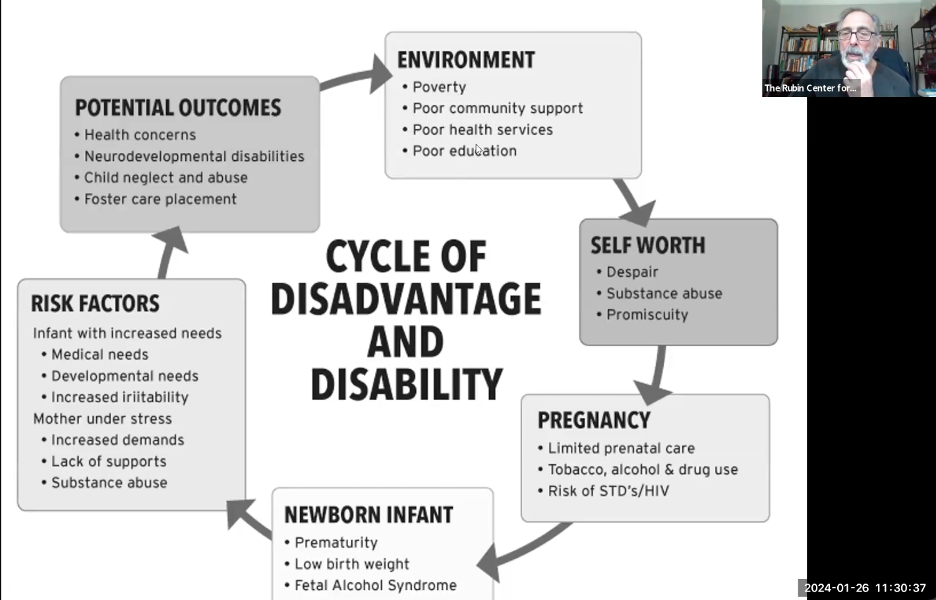

Figure 1: Initial Cycle of Disadvantage and Disability

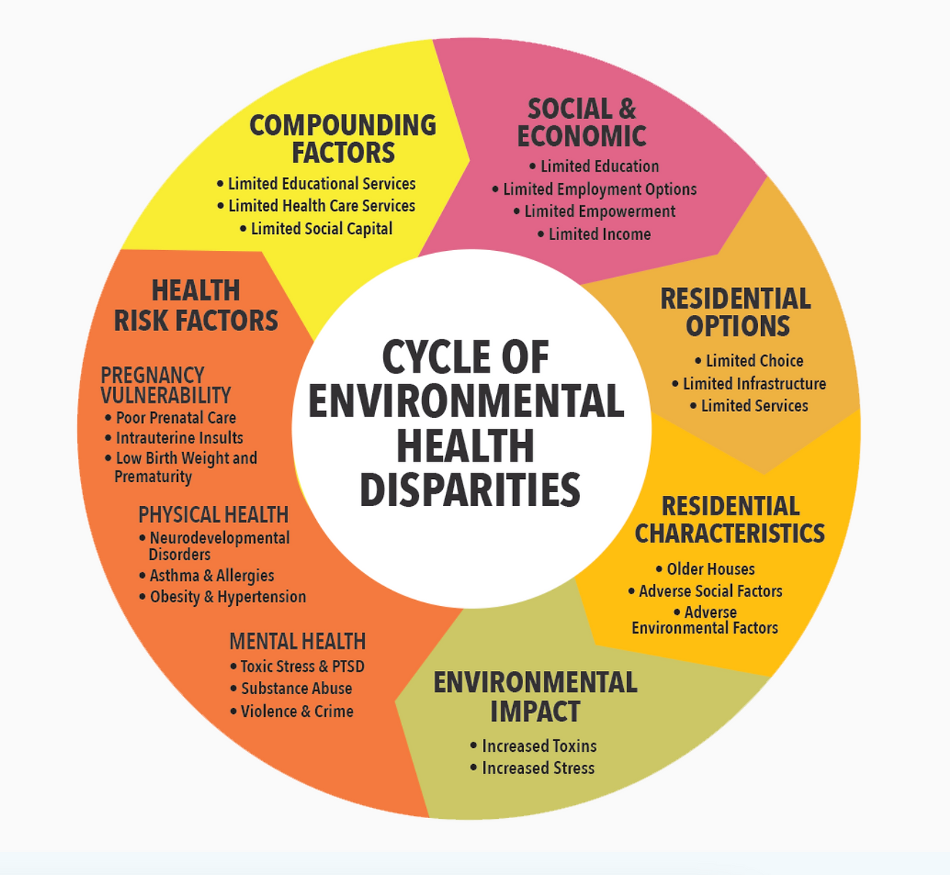

Figure 2: Recent Cycle of Environmental Health Disparities

LR: So now you can see the evolution of this concept. So this was the original cycle that I conceived of where poverty and these elements resulted in a feeling of a lack of future for the young people. They didn’t have a good education or role models. So they didn’t have a chance to get good jobs. And so they ended up feeling depressed, and what could you do to feel better? You could take drugs and have sex, and you feel better. But the problem is that the young women would get pregnant. They would not take care of themselves and would continue to smoke, drink alcohol, take drugs, and were at risk for sexually transmitted diseases and HIV. And then the babies would be born prematurely with low birth weight and even fetal alcohol syndrome. And these children would go on to have all these medical and developmental needs and be irritable. And the mothers are despairing and have to care for irritable children. These children end up with major health problems, developmental disabilities, neglect and abuse – and would end up in foster care. It was somewhat depressing. But I had the good fortune of getting funding for the students to do the survey which resulted in this finding.

I thought, how am I going to make a difference? If Lyndon Johnson had the whole Federal Government's budget at his disposal, and he could not win the war on poverty, how is Leslie Rubin going to defeat poverty with $10,000? I decided I would work with students – so I would ask faculty in different departments, do you have any students? I want them to develop projects to help break the cycle – in law, pediatrics, psychology, education, and public health. I had five students – each with a project – so I could give them stipends. They did their projects, and at the end, they presented at a little conference with 20 people. That was great. And then I did it again and got more and more funding. I had to struggle for funding until….

I will have to diverge. While I was doing all this, I met a pediatrician who knew I was interested in kids with developmental disabilities – and he was a toxicologist working with lead. He said, this is what happens – lead causes developmental disabilities. I want to work with you to see if we can collaborate to evaluate the impact of lead on children’s development. Unfortunately, he left soon after we started to collaborate, but have you heard about Howard Frumkin? He was head of Environmental Health at Emory. He was applying for the grant to start a PEHSU at Emory. He contacted me, a toxicologist, and a pulmonologist. And he created the first PEHSU in Atlanta. I started to get involved not only in poverty but the other environmental stuff with children’s health disparities. The group, which included the EPA and ATSDR representatives in Region 4 – they saw this model and said it would be interesting to add environmental factors to it, and then they funded it.

I changed it from Break the Cycle of Disadvantage and Disabilities to Break the Cycle of Children’s Environmental Health Disparities, and ever since then, the funding was secured. Every year, we recruit ten students to develop projects that will break the cycle.

JMK: That’s wonderful.

LR: One more piece of the puzzle that is worth telling you about – at the beginning of the PEHSU of Region 4, there was a situation of toxic waste in a town called Anniston, Alabama, just across the border from Georgia. The group there wanted to have a pediatrician come talk to pediatricians there about PCBs and lead and children’s health. We went to talk to the pediatricians, but there was one pediatrician in the front row – all the others were up top in the auditorium. They were not interested.

Soon we realized that it was not straightforward. What we were dealing with was an environmental justice issue. The people exposed to toxicants were poor Black people who worked in the chemical factories literally on the actual other side of the railroad tracks. It was not just a factor of exposure to a toxicant – but the business and White community didn’t want the spotlight shone on them because it was negative and turning people off business.

But they did hear about it, because the plaintiffs actually hired Johnnie Cochran of O.J. Simpson fame – and he won $700 million or something from the company, though everybody got about $100 dollars a person in the end. The lawyers took most of it. In that way, I got into the whole Environmental Justice world. So the program was not just the kids’ disabilities – not just socio-economic, not just the environmental aspect, but the whole political universe of children’s health and disability.

JMK: It’s a whole other world when you realize how systematic it is.

There's a through thread in everything that you have said, and it's something I spotted right away. You have such a wonderful warm affect. It comes across immediately when you introduce yourself to people. And it's so interesting – you described how, when you first saw patients on a ward, you thought about what their experience was, not just what the disease was. And so I just see that – that you were able to arrive at this understanding because you see people as whole people in a whole societal circumstance. And I wanted to mention that that is lovely.

LR: I often reflect on all the things I have done wrong and people I have hurt – too often. I really do – obsessing about that helps keeps me aware of what I do and how I do it so that I take pains to avoid offense. You know how sometimes when you get frustrated waiting in a line at someone behind the counter not knowing what they are doing. And you just say, that’s okay – it’s not going to kill me.

JMK: That is a wonderful attitude.

So you've already spoken to this a little bit. As a pediatrician, you talk to patients and parents about a topic that can generate fear and guilt. And I think some practitioners are averse to even talking to parents about toxic chemicals because of that. I wonder when you talk to parents about environmental exposures that their children have had or could have, how do you frame the problem so that it is productive and does not create too much anxiety?

LR: There are a couple of general principles I’ve learned over years – I promise, by making mistakes. And I try to learn from mistakes. First, it’s important to recognize that parents are anxious about their kids’ health and well-being. Number two, regardless of what the cause is, more often than not, mothers more than fathers, will blame themselves. They will say it is my fault – I did something wrong. Because of that, I take pains to tell them – it’s not something you did or didn’t do – this was something way out of your control – that caused whatever it is. We can only go forward and improve the situation with the resources we have available.

And the good news, I always say, is that we are living in the U.S. in 2024, and we know so much more and have better resources than we used to. I try to say it repeatedly – it’s not your fault, and you’ve done a great job – because you’re a parent, and you love your kids. I tell them that the most important thing is to love them and give them a good home. That is the most important thing; there is nothing that can substitute for that. What we add are things on top of that; we build on what you’ve done. So that’s my little speech. It’s kind of embarrassing when people know exactly what you are going to say. I say about the same thing every time because I know that is what the feeling is.

JMK: That is the wealth of experience that you have. Right? That's a lovely response to people. And I think what you say is largely true. Could parents prevent some exposures? Maybe some. But there are others they absolutely could not. It is systemic, right?

This gets to the next question, which is, if you were suddenly given magic powers, and could recreate U.S. policy regulating environmental chemicals, what would that policy look like?

LR: Oh boy. I think the ideal would be that any chemical that is available needs to be tested for safety – every chemical. That is ideal and impossible, really, but still, only testing a hundred of every thousand is just the tip of the iceberg. But the other part is that the chemical companies that produce the chemicals need to be more heavily scrutinized, regulated, and taxed. Generally, they make a lot of money from what they do, and part of the reason they haven’t moved on this issue is because the big companies have so much money.

My favorite story I relay about the tobacco industry is where the medical profession realized smoking makes you sick and causes lung disease and said we should ban tobacco. And the tobacco companies had to try to counter it, at first with ads with doctors smoking, saying that it helps them relax. Then they realized they couldn’t counter the science, which was really convincing, so what they did was deliberately cause doubt in people’s minds – you can say tobacco caused cancer, but what’s the proof? The man on the street will not know the research. So saying that creates doubt. The tobacco companies hired a marketing firm that determined that if you can create doubt – you can’t counter the evidence, but you can create doubt. And then they did the same thing with climate change.

JMK: Perhaps you are thinking of Naomi Oreskes’s book Merchants of Doubt. There was a documentary based on it, and that is pretty much what she lays out. And you know a few scientists created doubt on tobacco, climate change, environmental chemicals of all kinds, and acid rain. The list is long, and they have a playbook that they repeatedly deploy, and they still are doing it.

What do you think will be the status of children's health in 2050?

LR: I hope we’re not having the same battles at that time – I hope that we as a society begin to face realities – of climate change, and of the toxic environments that we have created. What is amazing is in the 1970s, at the height of the terrible air and water pollution in Cleveland, Chicago, and the St. Lawrence waterway – it was a toxic sludge – the Cuyahoga River caught fire a number of times. Eventually, the government said, let’s do something. So they implemented the Clean Air and the Clean Water Acts. I think we have to do that again.

Some great realization has to come. I’m not sure how Richard Nixon of all people made that happen. But something like that has got to happen. Some positive revolutionary action needs to come from the government. But, as I said, if Lyndon Johnson couldn’t win the war on poverty, what’s Leslie Rubin going to do? We need to try to build our little parts to make the big difference. It’s also—if we look at the complex issues – it’s not just toxicant and exposure – and then illness. Where, who, how, what factors led to that toxicant being present where children live and play? And how do we prevent them from being affected? It becomes quite the multidimensional phenomenon that does require really bold action and bold thinking.

JMK: I love that idea. That's a good adjective – to be bold. Okay. Last question, is there anything you would like to ask me about my experiences or my project?

LR: I would like to ask you lots, but it's 12:55, and I hope that we can have an opportunity for me to listen to you next time, because as you said, you've got your own story to tell, and I know about your daughter and how that has motivated you, but also, I don't know what the struggles were that you went through, and I can only guess. I do have a couple of my family members and two of my daughters who both have had cancer, but thanks to modern treatments, they are still around. So I understand.

JMK: Yes – maybe we can have lunch at the next CHPAC.

LR: Lunch sounds wonderful. Thank you for inviting me to do this – it’s the start of my memoirs. All right, Jean-Marie, thank you so much. Have a good weekend and keep up your good work. Thanks for telling me about the Merchants of Doubt. I'll check it out, and I look forward to seeing you again on Zoom or in D.C. in May!